How to program efficiently using ChatGPT for psychology and neuroscience research

ChatGPT has exploded onto the social and academic sphere of influence. Amongst its many uses within academia is the ability to generate and analyse blocks of code in response to a user prompt. Such a transition from human-based feedback (e.g., GitHub, Stack Overflow) to AI-based feedback for code generation and correction has emphasized the need to provide efficient prompts. Levying anecdotal experience with generating code using ChatGPT in my own research, I briefly discuss simple rules for designing prompts in the field of psychology and neuroscience.

Introduction

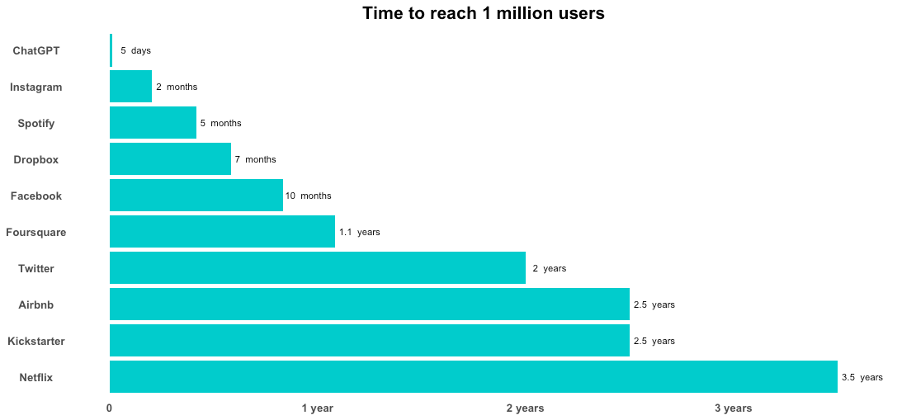

The introduction of ChatGPT (GPT-3 in 2022 followed by GPT-4 in 2023) to the public sphere has left an immediate impact upon modern society in a short period of time, with the platform reaching one million users far quicker than any service prior. Due to the flexibility and variability in its use, ChatGPT has been integrated into many job sectors, including academia. However, this has come as both a benefit and a bane towards academic research and teaching. Whilst students and academics can undoubtedly benefit from its role as a publicly available academic tutor, available at any time to provide shortened and simplified explanations of complex topics, the very same feature can also provide templated answers for marked examinations, altering the very nature of academic learning and grading (Anders, 2023; Cotton et al., 2023; Rudolph et al., 2023). Simultaneously, it’s pervasive use as a source of information and ability to provide feedback towards elements of experimental design and analyses (e.g., power calculations) has raised the question of whether ChatGPT should be credited as an academic author, forcing a stance on this topic to be given from major publishing journals (Curtis, 2023; Liebrenz et al., 2023; Nature Editorials, 2023).

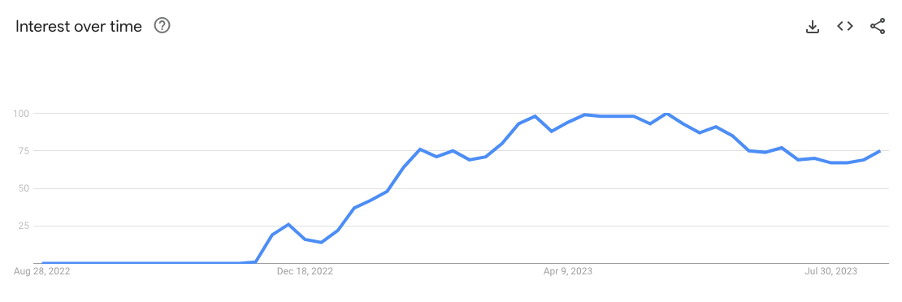

Interest in ChatGPT over time. Figure taken from a Google Trend search for ‘ChatGPT’ within the last 12 months (Search conducted on the 26th of August 2023). Numbers represent search interest relative to the highest point on the chart for the given region and time. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term. A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular. A score of 0 means there was not enough data for this term.

Time for major online services to reach 1 million users. Figure adapted by A.S. from an online version https://www.tooltester.com/en/blog/chatgpt-statistics/. Whilst Threads (a Twitter/X influenced platform from Meta) has since reached this milestone quicker than ChatGPT, it did so benefitting from an already prevalent user-base and brand.

A major influence on academic research is the ability of ChatGPT to provide workable code in response to a given prompt, and to debug faulty code given both the code and the associated error message, significantly improving programming efficiency. This is a consequence of the fundamental building block of ChatGPT, natural language processing (NLP), which enables the artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm to understand and process human language. Through a combination of machine learning algorithms and vast amounts of training data, the model learns patterns and relationships between words, phrases, and sentences, probabilistically selecting the next word within a generated response, time and time again. This same principle extends to programming languages by virtue of how both human and programming languages consist of their own syntax, grammar, and semantics. As ChatGPT recognises English, Italian, French and other cultural languages, it can generate blocks of code for a variety of programming languages including those most relevant to academics in the field of Psychology such as HTML, CSS, JavaScript, Julia, Python, and R. Such blocks of code are produced at a rate far beyond the capacity for human programmers. Whilst the working capacity of GPT-4 slows this production of code in comparison to GPT-3.5, sections of code are nevertheless generated in the order of seconds. Such a ‘real-time Stack Overflow’ is a significant tool in the arsenal of any academic, particularly beginners in the field of psychology for which an unfamiliarity with programming severely lengthens facets of data analysis or experimental design requiring programming experience. Being in this category, I found ChatGPT to be extremely beneficial, both improving productivity whilst also increasing my conceptual knowledge in the subject, as ChatGPT also provides additional information regarding the specific functions of the code when producing it.

However, whilst ChatGPT can provide meaningful code, it is not without fault. Indeed, whilst heralded as an academic ‘panacea’ (Quintans-Júnior et al., 2023) it also provides unusual errors in response to basic prompts. An overview of such errors (Borji, 2023), designates twelve categories, including ‘Reasoning’, ‘Logic’, ‘Math and Arithmetic’ and indeed ‘Coding’. Examples of this latter category can stem from two sources, either from a limitation associated with the machinery to which ChatGPT provides code from any given prompt, or a limitation of the prompt given to ChatGPT from the user.

Sources of user and model-related error in ChatGPT code generation. User-related errors such as not including relevant information in the prompt can lead to faults suspected to be the cause of the model but can be circumvented by changing the prompt. On the other hand, model-related errors are a direct cause of the model itself. In the first example on the left, the second line of code is entirely unnecessary, whilst the error below reflects the common scenario where ChatGPT provides faulty code. The latter can subsequently be corrected by inputting the error back into ChatGPT. Examples of ‘hallucinations’ on the right provide examples where faulty logic gives an incorrect response. In these examples, ChatGPT fails to provide the correct answer to the first question, answering Elvis Presley (the correct answer is Elvis Perkins), fails to label 17077 as being a prime number and fails to provide the correct answer for the number of socks (40). It should be noted that ChatGPT is constantly improving its accuracy in this domain, see (Chen et al., 2023) for changing responses to the second example. The example for the first question is taken from (OpenAI, 2023), third from (Plevris et al., 2023).

Ultimately, an examination of GPT’s replies to 517 questions from Stack Overflow, revealed that 52% of ChatGPT’s answers contain inaccuracies and 77% are verbose. In addition, ChatGPT’s answers were found on the whole to be more incorrect, significantly lengthy, and not consistent with human answers half of the time (Kabir et al., 2023). The authors posit that this stems from ChatGPT’s incapability to understand the underlying context of the question being asked, as it was found to rarely make syntax errors for code answers. Such errors can be avoided by providing meaningful, tailored prompts to begin with. Of course if such faulty or inaccurate code is generated, this code can be inputted back into ChatGPT ad infinitum to eventually reach a solution, but such recursive programming can be unnecessary if the initial prompt given is of adequacy. The subject of this short paper is therefore to focus on providing efficient prompts through three simple rules, resulting in a more efficient workflow. Whilst I will be using real-world examples from my own experience as an academic in the field of psychology, these rules are also transferable to other scientific disciplines.

Detail In, Detail Out

Despite ChatGPT’s ability to produce responses from basic prompts, its response is naturally limited by the information provided by the user. As noted in a recent discussion of ChatGPT’s potential as a programming support tool, this “depends on the user’s skill in giving instructions. The AI will not respond appropriately if user instructions are long, vague, or have lack of context” (Avila-Chauvet et al., 2023). Modifying the adage of ‘Garbage In, Garbage Out’, programming with GPT often reflects ‘Detail In, Detail Out’. Take the following example in which I had asked for a series of plots to be generated from some data that I had directly inputted into ChatGPT. Whilst the data itself was recognised; I had neglected to provide information regarding the filename. As such, ChatGPT defaulted to ‘data.csv’ as the input. On another example, it defaulted to “your_file_path.csv”. This is a simplistic overview of a tendency to generalise, to which ChatGPT will default if not instructed otherwise. Relatedly, ChatGPT has also inferred from unspecific prompts, to produce the relevant code in Python, when R was preferred.

The same principle also applies when debugging errors using feedback from ChatGPT. Solely providing the error message generated, in addition to the code can result in a solution, but a solution can be tailored to your specific problem by providing the actual structure of the data being acted upon. For example, specific data checks can be inferred where the data were previously inputted into ChatGPT. Such prompts are indeed possible without providing the data, but as prompted by the AI model itself, the more information that is provided, the more relevant the outputted code will be. And finally, the level of detail impacts how data is visualized. Akin to two artists, one asked simply to draw a face, versus another asked to draw a face of a happy 60-year old man, wearing glasses, with grey hair and a beard, the input given to ChatGPT significantly matters with providing relevant code in line with one’s request. Take the simple prompt below:

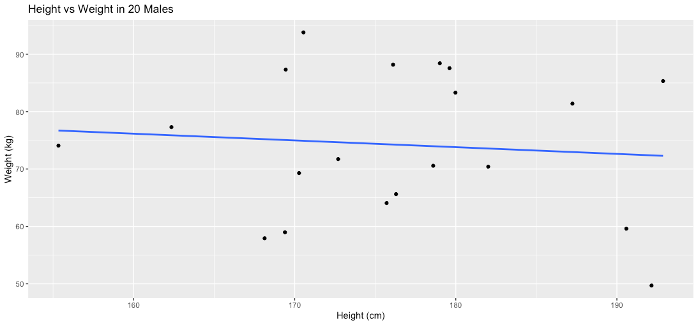

Prompt:

Generate a graph in R, plotting height versus weight in a group of 20 males.

To which the resulting code produces the following graph:

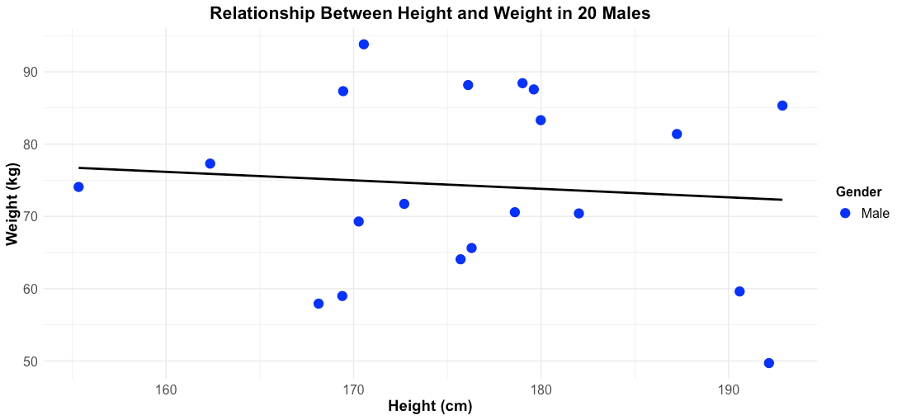

However, making a simple modification to the prompt can significantly affect how the data is presented. For example, adding the pretence to make the graph “suitable for a scientific publication” yields the following graph:

Note the addition of several components, including adding a colour scheme to individual data points, a more detailed plot title, and a legend. Such a feature again builds upon the AI’s understanding on what a graph for a scientific publication generally constitutes, and so it should be used with additional specific prompts when generating graphs for this specific purpose.

Another example is given where I prompted the creation of a single column csv file with the following instructions:

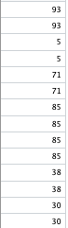

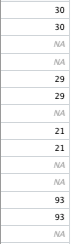

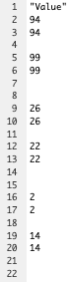

Generate a single-column csv file which has random values from 0-100 in each of the following rows: 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, 12, 15, 16, such that there is a gap of one between the first two pairs and a gap of two with the second two pairs. Continue to do this until the 348th row, which should also contain a number. Importantly, I would like for each pair of numbers to be the same. So, with the example above, 1 and 2 will be the same number, 4 and 5 the same, 8 and 9 the same and so on. Save this to a file called ‘single_sub_scores.csv’.

Whilst I specifically mentioned that there should be a gap between those rows mentioned, the output generated instead did not have any gaps.

Subsequently, I provided an example directly into ChatGPT which contained the exact structure required, and even despite this, and the confidence in the response:

Ah, I see what you’re asking for now. Here’s a modified version of the R script that includes a gap (NA) after every second pair of numbers:

The output was still incorrect. The following prompt generated a structure very similar (but not quite correct) to what was intended:

That’s not correct, the structure of your outputted csv does not match the structure of the column which I provided. There should be a single gap between the first two columns, and then a gap of two, followed by a gap of one, etc.

After both the example column and the column generated above were both inputted back into ChatGPT, it still was unable to create the required column. I then repeated this once more. Even though it would understand the intended pattern:

The pattern should indeed be two numbers, one empty row, two numbers, two empty rows, and so on.

It still repeatedly provided the wrong code a few more times, before finally providing the correct code.

This process, whilst significantly quicker than writing the code from scratch (for a programming novice I should mention), still took around 10-15 minutes to create. But how could one generate the correct code from a single prompt, and avoid repeatedly correcting ChatGPT? Well, simply asking ChatGPT for such a prompt provided the following:

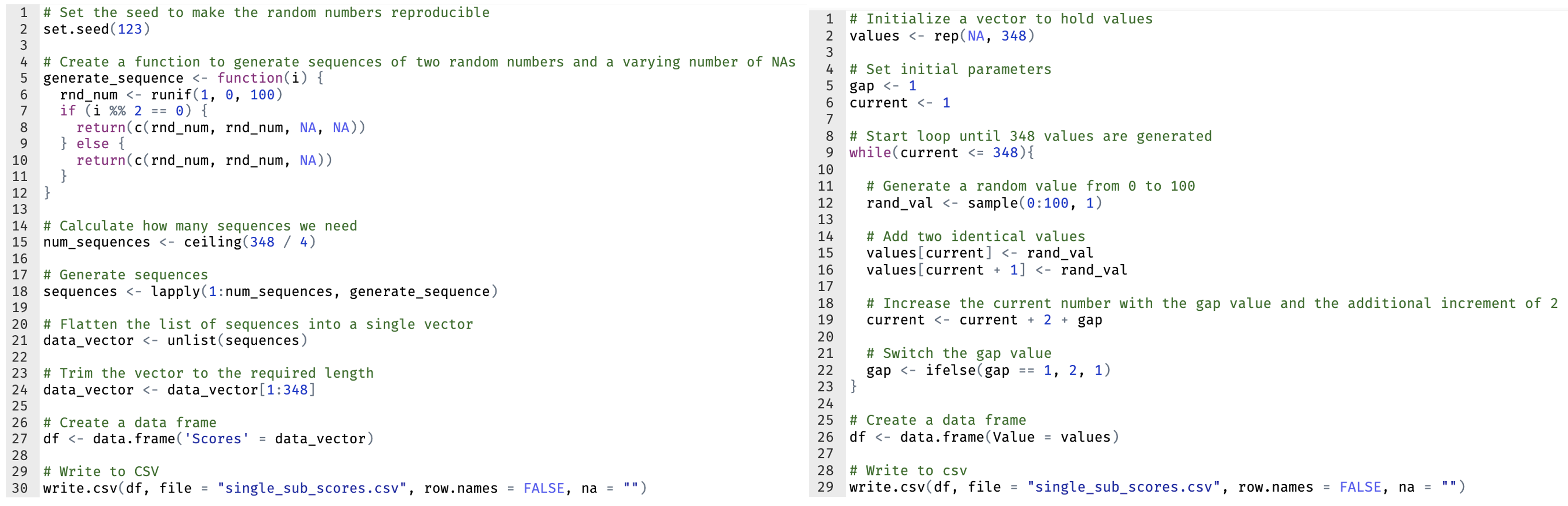

“Generate a R script that creates a csv file named ‘single_sub_scores.csv’ with a single column of 348 rows. The rows should follow this pattern: two rows containing the same random number from 0 to 100, one empty row, two rows with another random number, two empty rows, and so on. The pattern should keep alternating between one and two empty rows. Empty rows should be represented as NA in R but should appear as empty cells in the resulting csv file when opened in Excel.”

Interestingly, the code generated significantly differs from the correct code provided earlier, with the inclusion of a function to generate the number sequences. Below, the original code is on the right, with the code generated from the prompt above on the left.

But the correct output was generated, albeit not as integers.

In general therefore, one should provide the AI model with as much information as possible in the prompt. This is both to prevent generalisations in the case of ambiguity, and to increase the specificity of the code generated. Indeed, when asking ChatGPT if it would prefer to have such additional information regarding an issue it acknowledges the benefits of having specific information.

Prompt

Let me know if you need information regarding the structure and/or contents of either item.location or MRS.

ChatGPT

Yes, that would be helpful. Please provide the structure and contents (at least some sample data if it’s too large) of item.location and MRS variables. Also, if you can provide information about the expected operation, i.e., what the projection operation should result in, that would be very helpful in finding a solution.

Such detail may indeed span multiple prompts (see below), however the benefits observed outweigh the additional effort. Ultimately, the following structure/questions may be useful when planning one’s own prompts:

- Background for the prompt’s motivation

- Pre-text: Set the scene regarding your data. Describe your experimental design, methodologies, and statistical design (including programming language).

- Data: Describe the data. What data are you working/expecting to work with (i.e., neural, behavioural? What is the structure of the data?

- The prompt

- Prompt Outputs: What should be generated from the prompt? Including additional details (e.g., filename, specificity of syntax) can result in a more tailored output.

- Feedback

- Was the output generated in line with my needs? Provide specific feedback in the circumstance of AI-generated error or inaccuracy.

Rule 2 – Building complex scripts

Given the length and complexity of certain scripts, it may simply be unfeasible to provide a single minutely detailed prompt. Even though ChatGPT would eventually churn out the code in its entirety, a mistake would be propagated throughout, and any rectification would necessitate running the entire code from scratch, a time-consuming endeavour. Instead, separating code in chunks, and optimising each chunk in succession may be a useful strategy. Another example relates to the creation of a more complex script, where multiple relationships between parameters may be required. Such complex scripts can be difficult to initially visualise as a prompt but may instead be iteratively developed by setting a ‘basic environment’ and subsequently adding layers of complexity. Take the following example where a simulated dataset was created for a metacognitive decision-making task, in which I aim to ultimately distinguish between behavior and choice amongst those with high and low trait-metacognition. In the first prompt, I set the basic overview of the task:

I have a hypothetical task, in which participants start with 100 points in the bank. The objective of the task is to gain as many points as they can. The task is a visual discrimination task, which is split into a number of blocks. Each block will be titrated to have the participant’s performance at a certain level. For example, block one will be titrated to have a score of 60% whilst block 2 will have 70%, block 3 at 50% etc.

The values of the performance titration are not important however, just that it changes throughout the task. At the start of each block, we will measure the participants confidence, from a scale of 1-10. They will then have the option of placing a wager, which will again, be on a scale from 1-10 points. They will then complete the block, which will be titrated to a particular performance level. Finally, at the end of the block, they will be asked whether they would like to change their initial bet, which they can place from a scale of 1-10. We will run a total of 10 blocks. With this task in mind, please create a simulated dataset for a group of 30 participants.

The created dataset did not contain all my intended variables, and so I added more in the next two iterations:

I would now like to make some modifications to the task design. Before the pre_block_confidence for each block, I would like a measurement of how many points the person thinks they will gain or lose by the end of the block (pre_block_score_estimation). This will be on a scale from -10 to + 10. After each block, we will again measure confidence, but ‘post_block_confidence’ contrasting with the already mentioned ‘pre_block_confidence’. They will be measured in the same way, in a scale from 1-10. I will also measure their score estimation (post_block_score_estimation) at the end of each block, which will be before the post_block_confidence. I also would like to have some simulated scores at the end of each block, which follows the rules of the game, in that they can lose or gain a maximum of 10 points per trial, with 10 trials per block and 10 blocks in total.

Now incorporate some additional relationships between confidence, wager, revised bet and estimated score, based upon differences one would see within a sample. For example, create data for 15 participants who are high-risk and have low metacognition, and 15 who are safe-betting and have high metacognition.

Importantly, ChatGPT pulls upon its vast knowledge base to project assumptions regarding the task onto the two hypothesized groups:

Sure, to simulate the behavior of two groups of participants, we’ll have to introduce more rules into the simulation. Here are some assumptions that I’ll make to differentiate between the groups:

- High-risk participants with low metacognition:

- Are more likely to make high wagers (8-10).

- Have a wider range of pre and post-block score estimations (-10 to +10).

- Are less accurate in their score estimations (deviation from actual block scores will be higher).

- Show no significant change in their wagers after completing the block (low metacognition).

- Safe-betting participants with high metacognition:

- Are more likely to make low wagers (1-3).

- Have a narrower range of pre and post-block score estimations (-3 to +3).

- Are more accurate in their score estimations (deviation from actual block scores will be lower).

- Show significant reduction in their wagers after a loss and increase after a win (high metacognition).

However, it is important that if simulating data featuring populations with specific facets of behaviour, that this behaviour is reflected in line with your a priori hypotheses. One such hypothesis in this instance related to the wagering post and pre-blocks, something not automatically inferred by ChatGPT, and so it was added in a subsequent prompt.

Adjust the behaviour of both groups such that those with higher metacognition are more likely to lower their post_block_wager compared to their pre_bet_wager if it is more difficult, and more likely to raise it, if it is easier. There will not be the case for those with low metacognition.

Ultimately, by chaining multiple prompts, I was successfully able to simulate a relatively complex dataset, which fit the purpose of simulating potential results of the study as part of a presentation to funders. Whilst single, lengthy prompts can be provided to build a stronger ‘base’ to develop on, an iterative process is inevitable when creating complex scripts.

Rule 3 – GPT-4 vs GPT-3.5

On March 14th 2023, OpenAI released GPT-4, the successor to GPT-3.5. Whilst the two models share a lot of common features, GPT-4 features a significantly larger architectural model size than its predecessors, including GPT-3. This increased model size “helps improve its natural language processing capabilities, resulting in more accurate and relevant responses” (Koubaa, 2023). However, conversely to previous versions, the specifics behind GPT-4’s architecture were not revealed to the community. Indeed, in their technical report for GPT-4, OpenAI explicitly state that: “Given both the competitive landscape and the safety implications of large-scale models like GPT-4, this report contains no further details about the architecture (including model size), hardware, training compute, dataset construction, training method, or similar” (OpenAI, 2023).

What is known from the technical report is that GPT-4 outperforms GPT-3.5 in a variety of academic and professional assessments, particularly so in the:

- Uniform Bar Exam (90th percentile compared to the 10th percentile)

- LSAT (88th percentile compared to the 40th)

- SAT Math (89th percentile compared to the 70th)

- GRE Quantitative/Verbal (80th/99th percentile compared to the 25th/63rd)

Included among these tests were a series of coding problems provided through LeetCode (an online platform that provides a collection of coding challenges) in which GPT-4 performed better than GPT-3.5 in all levels of difficulty, including:

- easy (31/41 problems solved compared to 12),

- medium (21/80 compared to 8), and

- hard (3/45 compared to 0).

Given this clear improvement in performance, is there a benefit in using GPT-4 versus GPT-3.5 when programming in academia? From my experience, there is certainly an observable difference in the quality of the code generated. Take the earlier example where the following prompt was generated by ChatGPT to generate a specific pattern of numbers:

Prompt:

“Generate a R script that creates a csv file named ‘single_sub_scores.csv’ with a single column of 348 rows. The rows should follow this pattern: two rows containing the same random number from 0 to 100, one empty row, two rows with another random number, two empty rows, and so on. The pattern should keep alternating between one and two empty rows. Empty rows should be represented as NA in R but should appear as empty cells in the resulting csv file when opened in Excel.”

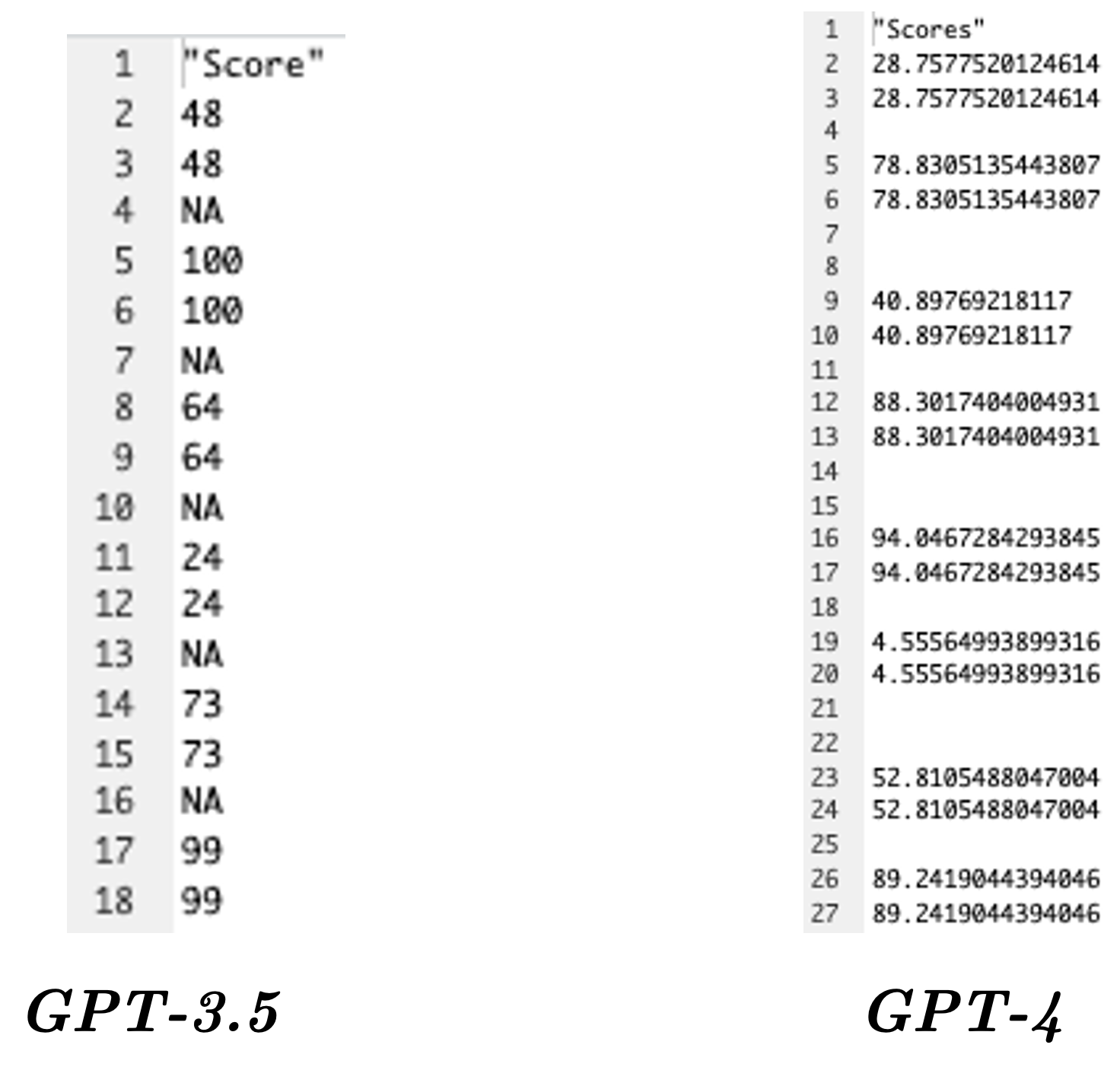

GPT-3.5 vs GPT-4 – End result of generated code

Interestingly whilst neither are correct, only GPT-4 creates the correct pattern. However, there are certain examples in which GPT-4 demonstrates a clear advantage over GPT-3.5. Take the following prompt, again involving the subsetting of data:

I have the dataframe ‘final_data_filtered’ in R, which has the following structure:(data structure provided)

I would like for you, for each Participant.Private.ID in rows where the column ‘Measure’ is ‘rating’, to plot ‘Response.pleasure’ - ‘Response.nutrition’ against ‘Response.value’. I would like for this to be plotted across the whole group (i.e., for all ‘Participant.Private.ID’ but also to plot the mean ‘Response.pleasure’ - ‘Response.nutrition’ against the mean ‘Response.value’ for each ‘Participant.Private.ID’.

Save the output as data frames so I can inspect them.

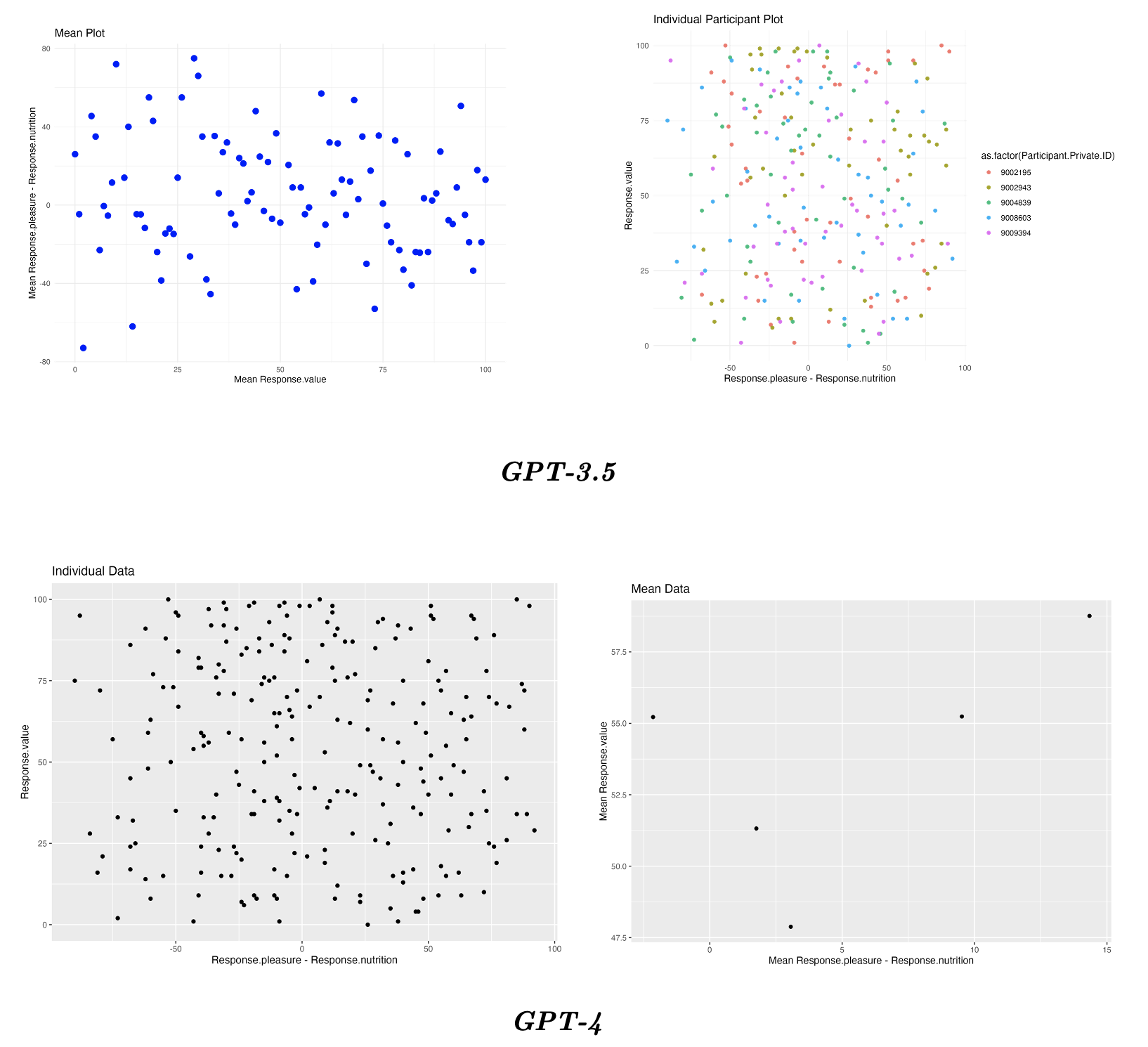

This is the corresponding data frame and plots for GPT-3.5 and GPT-4:

Note that whilst the individual level plots are the same (with GPT-3.5’s output even separating the different participants) only GPT-4 correctly creates the mean graphs for each participant, as seen in the graph on the right.

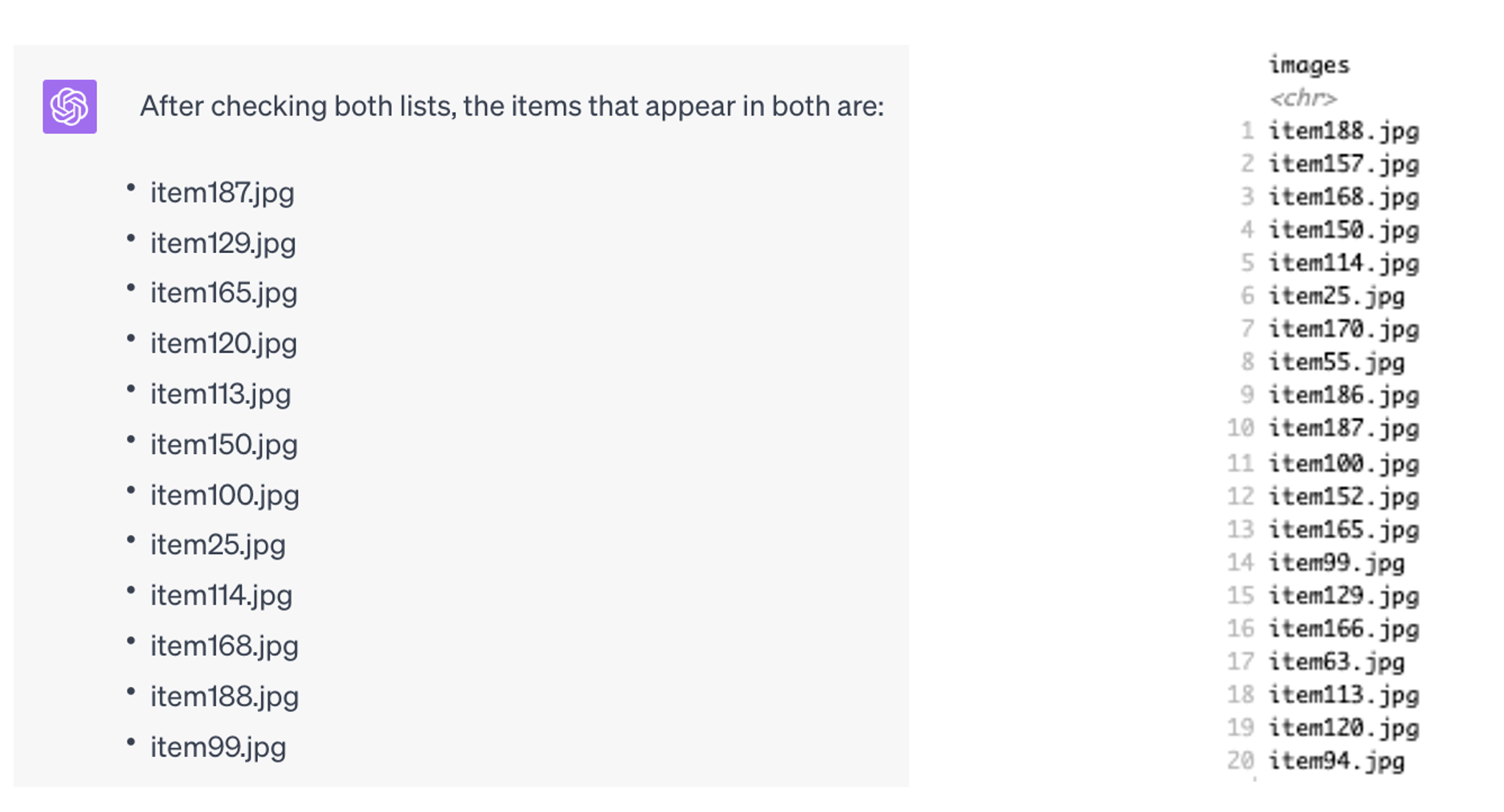

Inaccuracies also are visible when simply relying on the processing of the LLM itself. When asked to provide a list of unique items within two sets of 420 items (with each 60 unique items repeated 7 times in succession), GPT-4 incorrectly states that there were 46 unique items in list 1, and 44 unique items in list 2, when in fact there were 60 unique items in both list. In addition, when asked to list items present in both lists, it only lists 12, when there are in fact 20 (something it can accurately determine using programming).

Another important factor concerning GPT-4 is that it is currently only available through a subscription to ChatGPT Plus, a $20 (or equivalent) monthly subscription where the user also gains unlimited access to GPT-3.5 (it is not available to unsubscribed users during peak usage). The question remains as whether GPT-4 is worth the price. In my opinion, GPT-3.5 does significantly well for more basic coding needs, and whilst GPT-4 is more accurate for more complex programming tasks, both versions have the same underlying flaws with logic and inference. When asked itself to provide some examples of these limitations, six were given, of which four were relevant for psychologists and/or neuroscientists, and in line with this paper’s message.

Execution of Code: I can help generate code snippets based on the information provided, but I don’t have the ability to execute code or provide real-time debugging. This means I can’t run your code, see what the output is, and make adjustments accordingly.

Real-time collaboration or pair programming: My responses are stateless, which means I don’t have the ability to remember past interactions. This can make back-and-forth collaboration more challenging, as I won’t recall what was discussed or decided in earlier conversations.

Very complex, context-dependent tasks: While I can help with many coding tasks, very complex tasks that require deep understanding of a specific project’s context or intricate knowledge of a codebase could be challenging for me.

Writing large, complex programs: While I can help with small code snippets and even functions or modules, writing an entire complex software application with numerous interconnected parts is beyond my scope.

Conclusion

Programming is a necessary facet of academic research. The release of ChatGPT, with its ability to generate commented code in real-time in response to user-inputted prompts has in part shifted the necessity to learn the specific of coding, towards knowing how to provide efficient prompts to provide optimal code. Efficiency in this space is reflected by providing relevant information, asking the right questions, and choosing the right model. Doing so can reduce the primary limitations of inference and generalisation of ChatGPT when generating its response, a significant contribution towards incorrect code (Kabir et al., 2023).

References

Anders, B. A. (2023). Is using ChatGPT cheating, plagiarism, both, neither, or forward thinking?. Patterns, 4(3).

Avila-Chauvet, L., Mejía, D., & Acosta Quiroz, C. O. (2023). Chatgpt as a support tool for online behavioral task programming. Available at SSRN 4329020.

Borji, A. (2023). A categorical archive of chatgpt failures. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.03494.

Chen, L., Zaharia, M., & Zou, J. (2023). How is ChatGPT’s behavior changing over time?. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.09009.

Cotton, D. R., Cotton, P. A., & Shipway, J. R. (2023). Chatting and cheating: Ensuring academic integrity in the era of ChatGPT. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 1-12.

Curtis, N. (2023). To ChatGPT or not to ChatGPT? The impact of artificial intelligence on academic publishing. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 42(4), 275.

Editorials, N. (2023). Tools such as ChatGPT threaten transparent science; here are our ground rules for their use. Nature, 613(612), 10-1038.

Kabir, S., Udo-Imeh, D. N., Kou, B., & Zhang, T. (2023). Who Answers It Better? An In-Depth Analysis of ChatGPT and Stack Overflow Answers to Software Engineering Questions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.02312.

Koubaa, A. (2023). GPT-4 vs. GPT-3.5: A concise showdown.

Liebrenz, M., Schleifer, R., Buadze, A., Bhugra, D., & Smith, A. (2023). Generating scholarly content with ChatGPT: ethical challenges for medical publishing. The Lancet Digital Health, 5(3), e105-e106.

OpenAI. (2023). GPT-4 Technical Report. https://cdn.openai.com/papers/gpt-4.pdf

Plevris, V., Papazafeiropoulos, G., & Rios, A. J. (2023). Chatbots put to the test in math and logic problems: A preliminary comparison and assessment of ChatGPT-3.5, ChatGPT-4, and Google Bard. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.18618.

Quintans-Júnior, L. J., Gurgel, R. Q., Araújo, A. A. D. S., Correia, D., & Martins-Filho, P. R. (2023). ChatGPT: the new panacea of the academic world. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical, 56, e0060-2023.

Rudolph, J., Tan, S., & Tan, S. (2023). ChatGPT: Bullshit spewer or the end of traditional assessments in higher education?. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching, 6(1).