When knowing about cognitive neuroscience can make you a millionaire

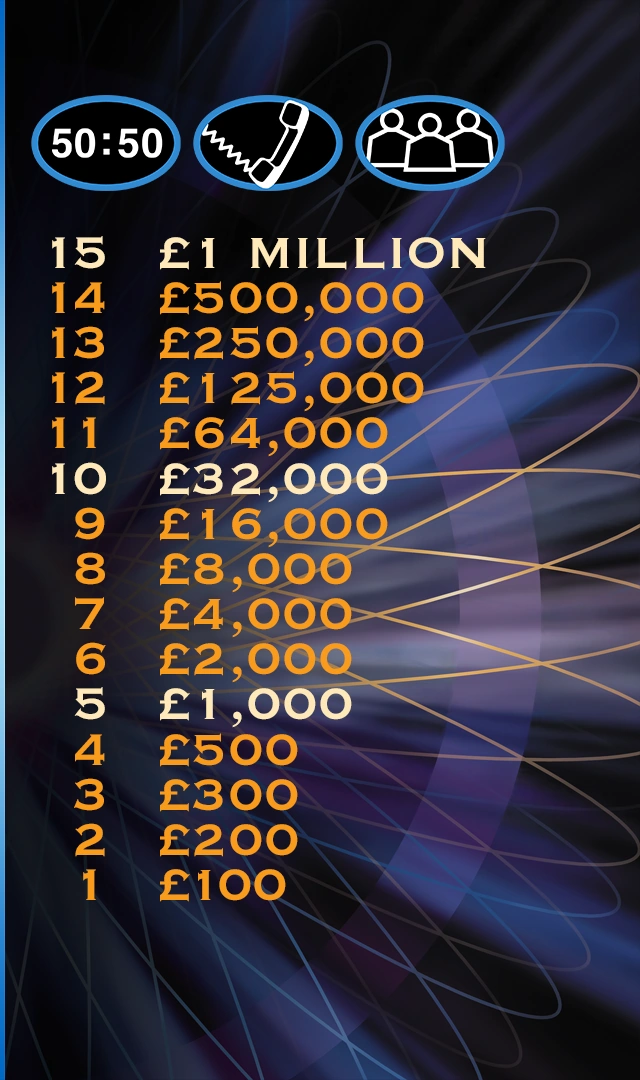

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? (WWTBAM), is arguably the most famous gameshow of the early to mid-2000’s. Beginning in 1998 on UK television, it quickly became a cultural hit, spreading internationally with many adaptations. For those unfamiliar with the show, contestants must answer 15 trivia questions, each with four possible answers, one right and three wrong. They may choose to walk away at any point, otherwise if they choose to answer and are wrong, they fall back to the most recent checkpoint (1,000 or 32,0001. To help them along the way, contestants have three lifelines

- Ask the Audience (where the audience is polled who each provide their guess on which answer is correct)

- 50:50 (where you can choose to remove two of the options)

- Phone a Friend (where you have 30 seconds to talk with a friend who can advise you on making your choice)

The classic Millionaire moneytree - example taken from UK Millionaire (1998)

Whilst only requiring 15 answers to win the top prize of 1 million, this has proven particularly difficult to achieve, with only 6 winners recorded on the British Millionaire, and 15 in the US adaptation over thousands of episodes across 25 years2.

Million-plus questions

But despite the moniker, there have been a few occasions where contestants could actually win more than a million. For a while in the ‘Primetime’ version of US Millionaire for example, the jackpot accumulated by $10,000 for each episode where there was no winner. Subsequently, there were four instances where a contestant made it to the final question, and was faced with a question worth more than 1 million.

Gary Gambino was the first, facing a question for exactly $2 million on March 1, 2001:

“Who is the only winner of the Nobel Peace Prize to decline the prize?”

(A) Albert Schweitzer

(B) Le Duc Tho

(C) Andrei Sakharov

(D) Aung San Suu Kyi

Gary did not know and decided to walk away with $500,000.

A month - and 14 episodes later - on April 1st, David Stewart faced a question for $2.14 million:

“People who have a marked physical reaction to beautiful art are said to suffer from what syndrome?”

(A) Proust Syndrome

(B) Jerusalem Syndrome

(C) Stendhal’s Syndrome

(D) Beckett’s Syndrome

David actually still had two lifelines to use: ‘Ask the Audience’ and ‘Phone a Friend’. Asking the audience didn’t help much, as you might expect for such a difficult question - as they were split quite evenly 26%, 15%, 32% and 27% across the four options. He decided to phone a friend, but faced a dilemma, one was an artist and the other a psychologist! His decision to go with the psychologist was unfortunately not vindicated as they had no idea! He ultimately also decided to walk away with the $500,000.

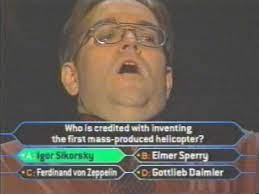

Just nine days later, on April 10, Kevin Olmstead became the third, the jackpot now worth $2.18 million. Here is the question he faced:

“Who is credited with inventing the first mass-produced helicopter?”

(A) Igor Sikorsky

(B) Elmer Sperry

(C) Ferdinand von Zeppelin

(D) Gottlieb Daimler

He immediately knew the answer and answered correctly, becoming the single largest winner in gameshow history up until that point (he would later be overtaken by Jeopardy titan Ken Jennings).

Realising that you've just won $1 million

After Kevin’s win, no one reached the million+ dollar question for 5 months. It was only until September 7, 2001 where Ed Toutant became the fourth and final contestant. He was given this question for $1.86 million:

“During WWII, U.S. soldiers used the first commercial aerosol cans to hold what?”

(A) Cleaning fluid

(B) Antiseptic

(C) Insecticide

(D) Shaving cream

Ed used his 50:50 before ultimately choosing the correct answer. His run - apart from being the final case where a player won more than a million on WWTBAM - was memorable for another reason. He was originally a contestant in January of that year, where the jackpot was $1.86 million (having not yet been won by Kevin Olmstead). He was playing for $16,000 with the following question:

“Scientists in England recently genetically altered what vegetable so it glows when it needs water?”

(A) Potato

(B) Tomato

(C) Cabbage

(D) Carrots

After asking the audience, who voted 64% for Tomato, he decided to go with that as the answer. However, they was wrong, the correct answer was Potato. That seemed to be that, but after doing some research he discovered a few things that could dispute the question entirely:

- The experiment had actually been done in Scotland, not England

- There was ongoing research with doing the same in tomatoes

As a result, he contacted the producers of the show, who agreed that he should be invited back. When he finally played again, he not only started back where he was at $8,000 (rather than starting from the beginning), he was re-awarded his ‘Ask the Audience’ lifeline, and the jackpot was restored to $1.86 million, which is what he was playing for at the time of his original run. Who would have thought that he would end up winning!

Flawed questions

This brings us into the curious scenario of flawed questions. The questions on WWTBAM are often set by trivia experts who - most of the time - are able to provide clear questions, with 3 definitively wrong and 1 definitively right answer. But this isn’t always the case. Whilst Ed’s is one of the more well-known examples, there are plenty of other cases where the question was subsequently challenged.

There are also different categories of flawed questions, including questions with multiple correct answers and questions with no correct answers! Here are some examples.

In the Austrian adaptation of Millionaire, contestant Peter Prinz in March 2002, for €15,000, was asked:

“Who won a silver medal in swimming at the Olympic Games in 1952?”

(A) Johnny Weissmüller

(B) Bud Spencer

(C) Gunther Philipp

(D) Bruno Kreisky

After choosing (A) incorrectly (the correct answer was Bud Spencer), Peter decided to learn more about the topic after the show. It transpired that Spencer had reached the semi-final of the 100m freestyle but did not win a silver medal in 1952, with Hiroshi Suzuki winning it instead!

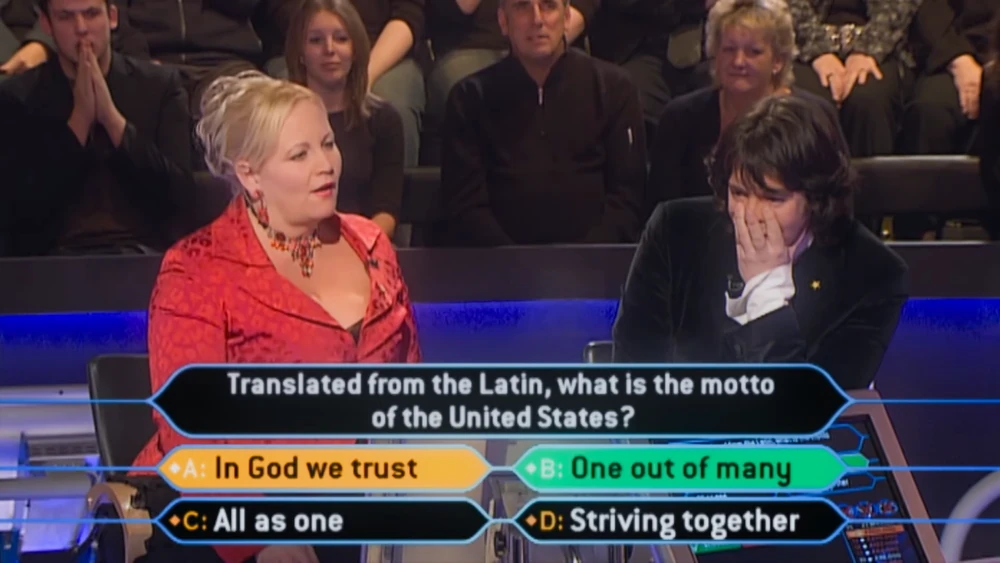

In the UK version, Laurence and Jackie Llewelyn Bowen - playing as a duo in February 2006, had actually made it all the way to the £1 million question, where they were asked:

“Translated from the Latin, what is the motto of the United States?”

(A) In God we trust

(B) One out of many

(C) All as one

(D) Striving together

Choosing to answer (A), they were horrified to be told that the correct answer was (B). However, it was later clarified that whilst “One out of many” was indeed the original motto of the United States, having Latin origins (E pluribus unum), but since 1956, the US were also using “In God we trust,” as a national motto, which did not have Latin origins. They were ultimately invited back, and faced another million-pound question, which they ultimately decided to walk away from.

Realising that you've just lost £468,000

Speaking of questions with more than one correct answer, also on the British version of Millionaire, on September 8, 2001, Stephen Parker faced this question for £64,000:

“What was the middle name of 18th century-born playwright Richard Sheridan?”

(A) Brinsley

(B) Butler

(C) Blake

(D) Boynton

Stephen answered (B), but it was revealed that the correct answer was (A). As a result, Stephen left with £32,000. However, it turns out that Richard Sheridan’s full name was Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan! He was invited back a month later, and was actually allowed to continue playing from £64,000, accepting his original answer as being correct. He walked away on the next question.

The Llewelyn Bowen and Parker questions are both examples where multiple options could have been accepted as correct, due to the vagueness of the question. In these and other cases, the ambiguity of the question was acknowledged, with the contestant being invited back soon after. However, there is one specific example for which this was not acknowledged at the time, and is still yet to be over twenty years later.

‘Super Millionaire’ and the flawed Million Dollar Question

In 2004, the US adaptation of Millionaire introduced a more extravagant version of the classic game. ‘Who Wants to Be a Super Millionaire’ (shortened to ‘Super Millionaire’) was a short-lived version where contestants now played for an ultimate prize of $10 million rather than the usual low-stakes of $1 million. The general format still remained, with 15 questions now separating you from a SEVEN-figure payout.

| Question No. | Correct Answer Value | Amount Lost for a Wrong Answer |

|---|---|---|

| 15 | $10,000,000 | $4,900,000 |

| 14 | $5,000,000 | $2,400,000 |

| 13 | $2,500,000 | $900,000 |

| 12 | $1,000,000 | $400,000 |

| 11 | $500,000 | $0 |

| 10 | $100,000 | $45,000 |

| 9 | $50,000 | $25,000 |

| 8 | $30,000 | $15,000 |

| 7 | $20,000 | $5,000 |

| 6 | $10,000 | $0 |

| 5 | $5,000 | $4,000 |

| 4 | $4,000 | $3,000 |

| 3 | $3,000 | $2,000 |

| 2 | $2,000 | $1,000 |

| 1 | $1,000 | $0 |

However, the questions were noticeably more difficult. To help out, an extra two lifelines were introduced, but only made available if contestants reached the $100,000 mark (question 10).

- Double Dip where players could make two choices instead of only one. However, contestants would have to commit to the question if deciding to use it.

- The Three Wise Men, a panel of three experts similar to ‘Phone a Friend’ where they would have 30 seconds to advise the contestant on which answer to choose

You may have realised that – in theory - a contestant could guarantee a correct answer by using both the 50:50 and Double Dip lifelines on the same question! Whilst it was brought up during the episodes, this never in fact happened.

There were only 12 episodes of Super Millionaire, with 31 contestants taking part. Of those 31, just 5 saw a million-dollar question. But before jumping into the case of the flawed million-dollar question, it is worth revisiting the run of one of the other 5.

I had mentioned above that only four people had the opportunity to answer a question which would have won then more than the million-dollar jackpot:

-

Gary Gambino ($2.00 million) – March 1, 2001

-

David Stewart ($2.14 million) – April 1, 2001

-

Kevin Olmstead ($2.18 million) – April 10, 2001

-

Ed Toutant ($1.86 million) – September 7, 2001

However, there was actually a 5th instance, when Robert ‘Bob-O’ Essig became the first - and only player - to win a million dollars on Super Millionaire. After doing so, he faced a question for $2.5 million:

“The last known sighting of labor leader Jimmy Hoffa was on July 30, 1975 at what Michigan restaurant’s parking lot?”

(A) Machus Red Fox

(B) Big Daddy’s Parthenon

(C) Beau Jacks Restaurant

(D) Salvatore Scallopini

Bob ultimately didn’t know the answer and decided to walk away with the million. It’s interesting to know what the questions for the $5 million and $10 million would have been, but we may never know! Bob was only the second player to take part in Super Millionaire, so you would be forgiven for thinking that at least one person would have gone further, or even all the way!

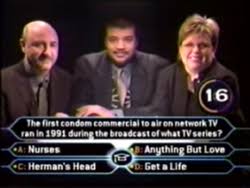

Bob had followed the first contestant on Super Millionaire, Todd Kim. Todd was a law graduate, earning both his BA and JD from Harvard and was an executive editor of the Harvard Law Review. And as the very first contestant, no one quite knew what to expect from his run, but he seemed to be doing pretty well. In fact, he didn’t use a single lifeline on his first 8 questions. However, on Question 9 (for $50,000) he used his 50/50 and in the very next question (for $100,000) burned through the ‘Ask the Audience’ and ‘Phone a Friend’ lifelines.

Todd Kim preparing to be the first contestant on Super Millionaire

But Todd had made it to the second checkpoint, and was now guaranteed at least $100,000. Answering just one more question would increase this 5-fold. However, this question was particularly fiendish:

“The first condom commercial to air on network TV ran in 1991 during the broadcast of what TV series?”

(A) Nurses

(B) Anything But Love

(C) Herman’s Head

(D) Get a Life

Todd didn’t know and used his newly acquired ‘Three Wise Men’ lifeline (as he had just reached the $100,000 checkpoint). The wise men consisted of author Anthony DeCurtis, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson and previous Millionaire winner Nancy Christy. They weren’t sure but ultimately advised Todd on a particular answer. Todd then used his Double Dip, and whilst getting the first guess wrong, the second one was right.

Todd's 'Three Wise Men' - Anthony DeCurtis, Neil deGrasse Tyson and Nancy Christy

He then faced a question for $1 million, being the first person to play for a million on Super Millionaire, already as the first contestant:

“Neurologists believe that the brain’s medial ventral prefrontal cortex is activated when you do what?”

(A) Have a panic attack

(B) Remember a name

(C) Get a joke

(D) Listen to music

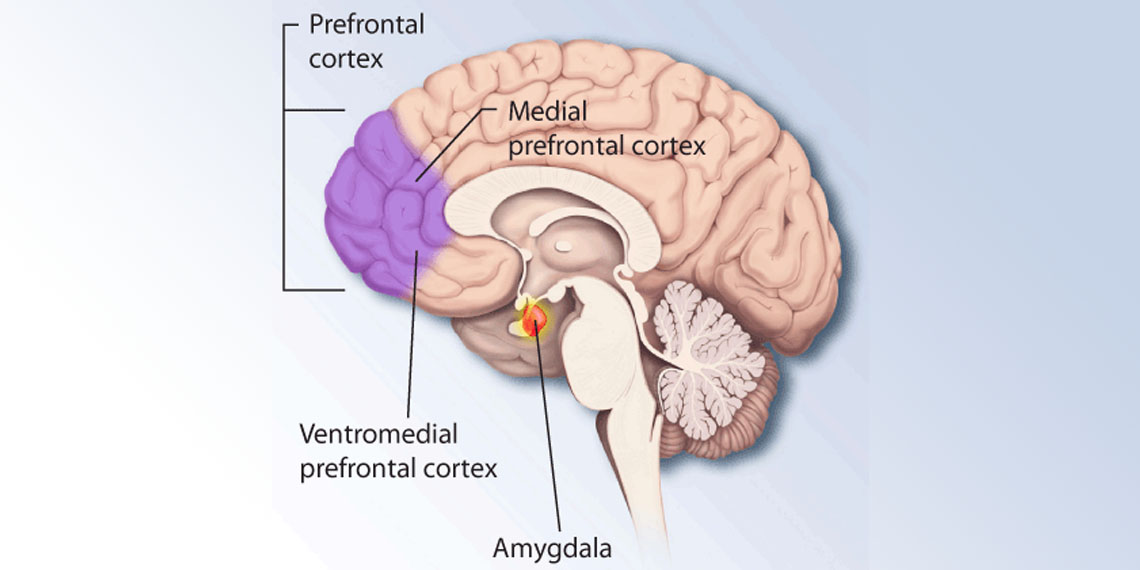

Todd had no idea - unsurprisingly - the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) is a region of the brain only psychologists and neuroscientists would even know the name of, never mind the function. He decided to eventually walk away with the $500,000.

When being a cognitive neuroscientist may actually be useful

The answer was revealed to be (C) - Get a joke. But is this the right answer? Or is this another case of a flawed question?

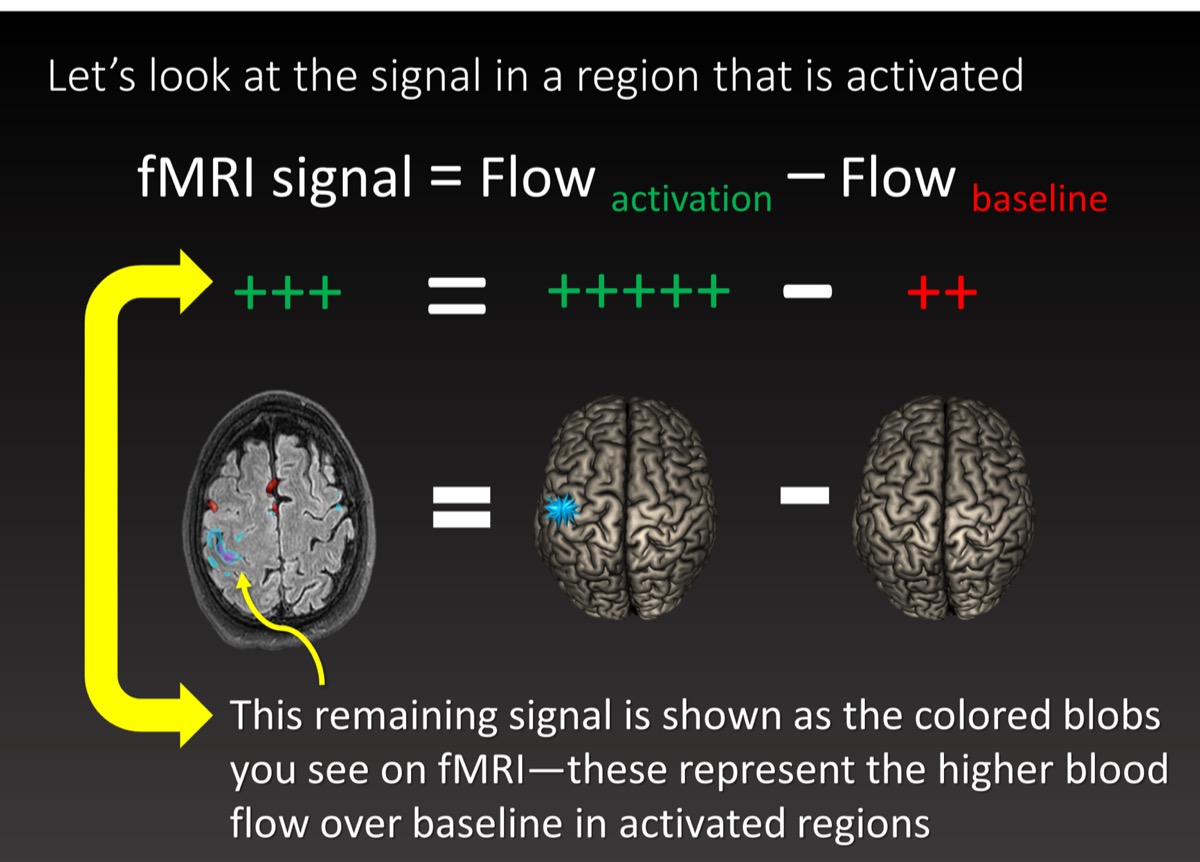

There are actually several problems with this question. The first is it’s ambiguity. To say that there is a single correct answer and three incorrect answers suggests that the other three actions do not activate the vmPFC. But that isn’t true. The vmPFC (as with all other brain areas) is active during all four processes. In fact, it’s active during any cognitive process! It’s too naive to state that parts of the brain are discretely ‘on’ and ‘off’, and too vague to state that they ‘activate’ and ‘deactivate’ in response to a stimulus. Instead, one can say that regions of the brain increase and decrease in their magnitude of activity relative to some baseline condition (i.e., when doing nothing) which happens - to varying degrees - for a particular cognitive process. Ultimately, in cognitive neuroscience, we are interested in determining exactly that, the statistical significance of changes in activity measured across two or more experimental conditions.

As a simple case, one could define two conditions: getting a joke (condition A) vs. listening to a joke but not getting it (condition B). Instead of asking “Is region X active?” (which is a moot questions as it always is), the question to ask is whether region X is more active during condition A than condition B. This is statistically tested using a contrast analysis between the two conditions.

fMRI (and neuroimaging in general) often relies upon measuring the relative change in brain activity between two (or more) conditions

So, the formatting of the question automatically renders the question moot, with all four answers technically being correct. A better phrasing of the question would perhaps be:

“Which of these cognitive processes is most typically associated with activity of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex?”

But again, there are flaws with this formulation of the question as well. If stating that a cognitive process is ‘more typically’ associated with a particular brain region, how can that be determined? You could do a meta-analysis (i.e. a study of studies) of the relevant neuroimaging literature to see which has a more robust association, but I will assume that such a meta-analysis was not consulted by the producers back in February 2004!

More worryingly, a quick search of the literature (which admittedly the majority of studies were published after 2004) will in fact show that the vmPFC is strongly implicated with memory, with vmPFC damage robustly affecting autobiographical memory recall (Bertossi et al., 2016; McCormick et al., 2018). By association, the vmPFC is also activated when listening to music if it triggers an autobiographical memory! (Janata, 2009) Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies further show that listening to popular familiar songs (Ford et al., 2016), as well as unfamiliar classical music (Trost et al., 2012) both lead to increased vmPFC activity, stemming from positive emotions such as nostalgia and tenderness (Hennessy et al., 2025; Trost et al., 2012).

Understanding whether the vmPFC is also active when having a panic attack is a bit trickier. Whilst the role of the prefrontal cortex more generally in panic disorder is well known, due to its involvement as part of the ‘fear network’ (Gorman et al., 2013) since the question distinctly mentions the process of having a panic attack, we will exclude typical study designs which would compare brain activity at rest between two patient groups (i.e., neurotypicals with panic disorder and healthy controls) or by inducing emotions representative of a panic attack (i.e., fear, anxiety). But, to run a study where participants are induced into a panic attack is ethically questionable!

However, we can draw on a few studies where this happened unexpectedly during the course of an experiment. In one case, two anxiety disorder patients spontaneously experienced a panic attack whilst undergoing fMRI scans. These patients demonstrated changes in activity of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) specifically when the panic attack occurred (Dresler et al., 2011). Similar instances also strongly implicate other regions of the ‘fear network’ including amygdala and insular cortex (Fischer et al., 1998; Pfleiderer et al., 2007; Spiegelhalder et al., 2009). So, whilst the prefrontal cortex is certainly involved in the fear response, we currently lack direct evidence that the vmPFC specifically changes in activity during a panic attack.

Areas of the prefrontal cortex - including vmPFC

So, we can state that some of the ‘incorrect’ answers are actually correct. But is the ‘correct’ answer correct? Is the vmPFC indeed activated when we ‘get a joke’? Evidence actually suggests that it is humour appreciation (i.e., the amusement with getting a joke) and not humour comprehension which is precisely related to vmPFC activity (Adamczyk et al., 2019; Chan, 2024). Conversely, evidence suggests that the midbrain and amygdala are more strongly associated with the actual element of ‘getting a joke’ (Chan et al., 2016, 2018; Nakamura et al., 2018). So, it turns out that not only were the wrong answers correct, but the right answer was incorrect!

Ultimately, the scientifically informed answer to Todd’s question would be either (B) or (D), not (A).

What can we take away from all of this? Todd will most likely not be invited back to complete his game 21 years later. Having had a successful career in law, recently as the United States Assistant Attorney General for the Environment and Natural Resources Division under the Biden Administration, and the first solicitor general of the District of Columbia for more than a decade before that, I doubt that he would need the money. But we can learn that claims in science, - particularly cognitive neuroscience - need to be specific and precise. It is far too simplistic to state that parts of the brain are ‘activated’ and ‘deactivated’, and are involved in one function but not another. That’s not to say that the brain should be excluded from trivia questions - far from it in fact3 - but they need to be held to more scrutiny than most.

References

Adamczyk, P., Wyczesany, M., & Daren, A. (2019). Dynamics of impaired humour processing in schizophrenia–An EEG effective connectivity study. Schizophrenia Research, 209, 113-128.

Bertossi, E., Tesini, C., Cappelli, A., & Ciaramelli, E. (2016). Ventromedial prefrontal damage causes a pervasive impairment of episodic memory and future thinking. Neuropsychologia, 90, 12-24.

Chan, Y. C. (2016). Neural correlates of deficits in humor appreciation in gelotophobics. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 34580.

Chan, Y. C., Hsu, W. C., Liao, Y. J., Chen, H. C., Tu, C. H., & Wu, C. L. (2018). Appreciation of different styles of humor: An fMRI study. Scientific reports, 8(1), 15649.

Chan, Y. C. (2024). 4 The Neuroscience of Humor. De Gruyter Handbook of Humor Studies, 2, 65.

Dresler, T., Hahn, T., Plichta, M. M., Ernst, L. H., Tupak, S. V., Ehlis, A. C., … & Fallgatter, A. J. (2011). Neural correlates of spontaneous panic attacks. Journal of neural transmission, 118, 263-269.

Gorman, J. M., Kent, J. M., Sullivan, G. M., & Coplan, J. D. (2013). Neuroanatomical hypothesis of panic disorder, revised (pp. 245-257). Routledge.

Fischer, H., Andersson, J. L., Furmark, T., & Fredrikson, M. (1998). Brain correlates of an unexpected panic attack: a human positron emission tomographic study. Neuroscience letters, 251(2), 137-140.

Ford, J. H., Rubin, D. C., & Giovanello, K. S. (2016). The effects of song familiarity and age on phenomenological characteristics and neural recruitment during autobiographical memory retrieval. Psychomusicology: Music, Mind, and Brain, 26(3), 199.

Hennessy, S., Janata, P., Ginsberg, T., Kaplan, J., & Habibi, A. (2025). Music‐Evoked Nostalgia Activates Default Mode and Reward Networks Across the Lifespan. Human brain mapping, 46(4), e70181.

Janata, P. (2009). The neural architecture of music-evoked autobiographical memories. Cerebral Cortex, 19(11), 2579-2594.

McCormick, C., Ciaramelli, E., De Luca, F., & Maguire, E. A. (2018). Comparing and contrasting the cognitive effects of hippocampal and ventromedial prefrontal cortex damage: a review of human lesion studies. Neuroscience, 374, 295-318.

Nakamura, T., Matsui, T., Utsumi, A., Yamazaki, M., Makita, K., Harada, T., … & Sadato, N. (2018). The role of the amygdala in incongruity resolution: The case of humor comprehension. Social neuroscience, 13(5), 553-565.

Pfleiderer, B., Zinkirciran, S., Arolt, V., Heindel, W., Deckert, J., & Domschke, K. (2007). fMRI amygdala activation during a spontaneous panic attack in a patient with panic disorder. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 8(4), 269-272.

Spiegelhalder, K., Hornyak, M., Kyle, S. D., Paul, D., Blechert, J., Seifritz, E., … & Feige, B. (2009). Cerebral correlates of heart rate variations during a spontaneous panic attack in the fMRI scanner. Neurocase, 15(6), 527-534.

Trost, W., Ethofer, T., Zentner, M., & Vuilleumier, P. (2012). Mapping aesthetic musical emotions in the brain. Cerebral cortex, 22(12), 2769-2783.

Footnotes

1 - In the conventional format

2 - Counting Ike and Alan Barinholtz’ win in August 2024 as a single case

3 - Recently on an episode of UK Millionaire aired 11 May 2025, contestant Mike Hayes was asked for £250,000:

“Which part of the human brain, connected to the pituitary gland, is responsible for controlling heart rate and body temperature?”

The options were (A) Hypothalamus, (B) Amygdala, (C) Frontal lobe, (D) Hippocampus. He ultimately did not know and walked with £125,000.

Answers:

(B) – Le Duc Tho - Le Duc Tho was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1973 “for jointly having negotiated a cease fire in Vietnam” but declined as he felt the ceasefire conditions were violated by the US.

(C) – Stendhal’s syndrome – Writing under the pseudonym of “Stendhal”, Marie-Henri Beyle first described a profound reaction to art whilst traveling the early 19th century.

(A) – Igor Sikorsky – Sikorsky worked on his first helicopters in the 1930s and 40’s.

(C) – Insecticide – Designed by USDA researchers Lyle Goodhue and William Sullivan, the first mass produced aerosol cans contained insecticide and were used by soldiers in the Pacific theatre during WW2.

(A) – Machus Red Fox – Hoffa had scheduled for a meeting at the restaurant and was kidnapped after neither of the attendees turned up.

(D) – Herman’s Head – On November 17, 1991, FOX became the first national broadcast television network to run a condom commercial, a 15-second spot for its Trojan Extra Strength brand.

(A) – Hypothalamus – The hypothalamus is the part of the brain involved with regulating many important bodily functions including body temperature, hunger, fatigue, sleep and social behaviours.

Credits

Photos taken from the Millionaire Wiki and National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Functional MRI image by Lea Alhilali (https://radiopaedia.org/courses/neuroradiology-threads-by-lea-alhilali/pages/1848). Content is available under CC-BY-SA.